Why Do Amine-Containing Resins Discolor When Paired with UVAs?

In practical applications, many customers using polyurethane, epoxy, or other high-performance resins face a common frustration: the material looks excellent immediately after production, yet begins to yellow during storage, early-stage use, or even before formal weathering tests begin. Even when Ultraviolet Absorbers (UVA) and light stabilization systems are added to the formulation, yellowing persists and is difficult to mitigate simply by increasing the dosage.

Consequently, yellowing is often instinctively attributed to UV aging or dismissed as a result of using insufficient grades of light stabilizers. However, for amine-containing resin systems, the reality is often different. Extensive practical experience shows that this type of yellowing does not necessarily occur after long-term exposure, but rather forms before the material has been subjected to significant UV energy.

The root cause is not entirely UV light itself, but rather the chemical compatibility within the resin system. Specifically, the key factor determining appearance stability is whether the molecular structure of the UVA can remain stable in an amine-rich environment without undergoing acid-base reactions or structural side reactions with amine functional groups.

The Presence of Amines: A "Structural Fact" in Polymer Systems

In most high-performance resin systems, amines are not accidental impurities; they are an unavoidable part of the material dictated by its design and reaction mechanism.

In Polyurethane (PU) systems, while the primary structure of the final material consists of urethane bonds, tertiary amine catalysts—such as Triethylenediamine (TEDA)—are almost always used during production to control reaction rates, cell structure, or film formation. Furthermore, reactions between isocyanates and amines can generate polyurea structures; if amine chain extenders are used, the amine content in the system increases further.

In Epoxy systems, the role of amines is even more critical. While epoxy monomers themselves do not contain amines, over 80% of Bisphenol A-type epoxy formulations rely on amine hardeners for cross-linking. Whether using aliphatic amines (e.g., EDA, DETA) or aromatic amines (e.g., DDM, DDS), the final cross-linked network retains a significant amount of secondary and tertiary amine structures after reacting with epoxy groups. In other words, amines are not consumed; they are immobilized within the resin structure in different chemical forms, existing as long-term, basic functional groups.

In amino resins, such as urea-formaldehyde and melamine-formaldehyde, the resin is formed through the condensation of monomers that inherently contain amine or amide groups. These amine-related structures constitute the cross-linked backbone, meaning the cured material is naturally in a high-amine environment. Similarly, while Polyamide (Nylon) is considered a stable engineering plastic, its molecular chain consists of amide bonds and often retains terminal amine groups. Under high temperatures or long-term use, these terminal amines can participate in side reactions, threatening appearance stability. Polyurea systems, formed by the rapid reaction of isocyanates and amine-terminated polyethers, possess a high density of amine-derived functional groups and represent a classic high-amine chemical environment.

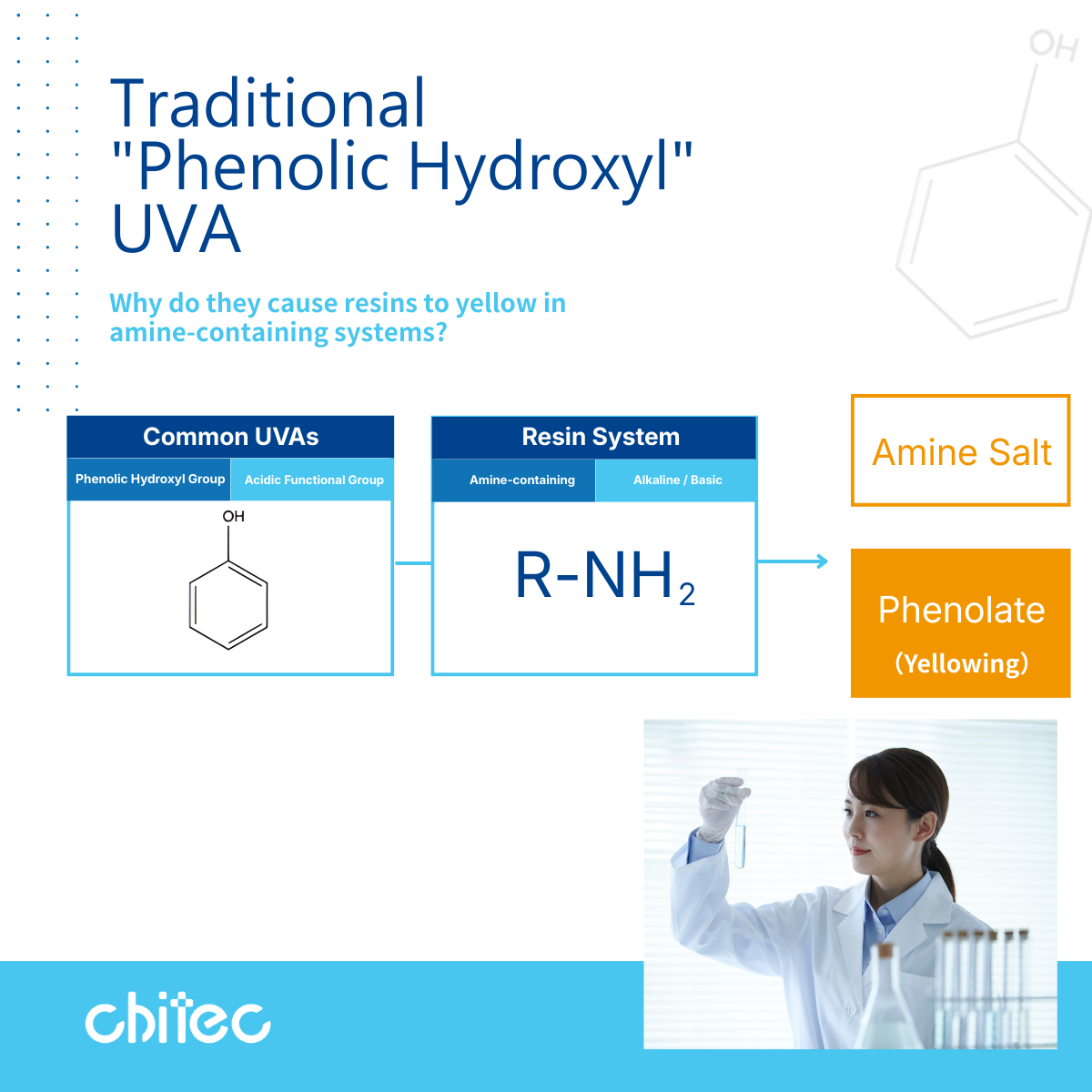

Why Do Traditional "Phenolic Hydroxyl" UVAs Fail in Amine Systems?

When exploring yellowing risks, the core issue is not UV absorption efficiency, but the predictable chemical interactions between molecular structures.

To effectively absorb UV light, most traditional UVAs incorporate a phenolic hydroxyl group into their molecular structure. This functional group is weakly acidic and generally stable in neutral or non-amine systems. However, when introduced into amine-containing resins, this acidic structure exists alongside basic amine groups within the same polymer environment for extended periods.

Under these conditions, the phenolic hydroxyl group easily undergoes an acid-base interaction with amine functional groups to form amine salts or phenolate side-products. These products often absorb visible light, manifesting as a progressive and irreversible yellowing of the material. Therefore, much of the yellowing attributed to "UV aging" actually stems from the structural incompatibility between the UVA and the amine-containing resin.

Insights from Epoxy Reaction Mechanisms: Why Amines Persist

Epoxy resin is one of the most misunderstood cases. A common question is: "If epoxy resin itself isn't an amine, why do amine-related issues occur?" The answer lies in the curing mechanism.

During the initial stage of curing, primary amines react with epoxy groups to undergo ring-opening, forming $\beta$-hydroxyamine structures. In this process, the amine does not disappear; it transforms from a primary amine to a secondary amine while introducing new hydroxyl groups, further increasing the chemical activity of the system. Subsequently, the secondary amine continues to react with epoxy groups to form tertiary amine structures, gradually building a 3D cross-linked network.

The key takeaway is that throughout the reaction, amines only change their chemical form rather than being removed. The final cured epoxy resin contains a high concentration of secondary and tertiary amine structures, resulting in a chemically basic environment. Pairing this with a phenolic hydroxyl-containing UVA makes yellowing a predictable outcome.

The Magnification Effect of N–H Type HALS

In practical formulations, epoxy systems are often paired with HALS (Hindered Amine Light Stabilizers) to improve weatherability. However, the mechanism of most N–H type HALS relies on a continuous regenerative cycle within the material.

In amine-cured epoxy systems, the persistent active amines and ionic by-products formed by amine interactions create an amine-rich environment. This environment can interfere with the normal HALS cycle—leading to salting, side reactions, or reduced regeneration efficiency—thereby weakening the light stabilization effect. Consequently, the combination of phenolic hydroxyl UVAs and N–H type HALS in amine-cured Bisphenol A epoxy resins often poses risks to both compatibility and long-term stability.

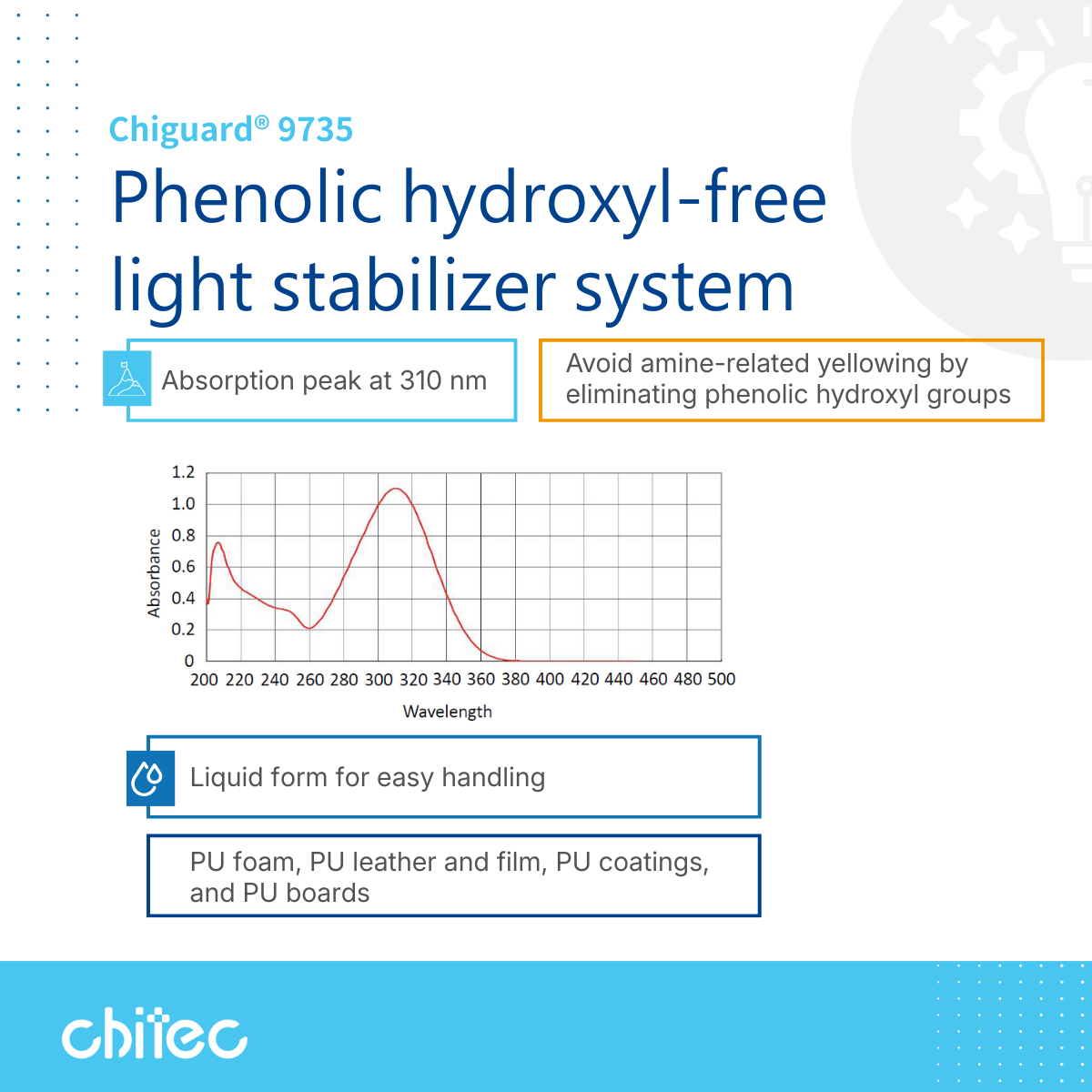

Why Chiguard® 9735 System is the Preferred Choice for Amine Systems

Based on the mechanisms above, the selection of UV absorbers for amine-containing resin systems should not be limited to absorption range or efficiency. Compatibility at the structural level is the only way to fundamentally reduce yellowing risks.

The core design feature of the Chiguard® 9735 light stabilizer system is that its molecular structure contains no phenolic hydroxyl groups. This allows it to absorb UV light effectively even in high-amine resin systems while avoiding the formation of salts or colored by-products. For formulators, this ensures more stable initial color and fundamentally reduces the risk of long-term yellowing and light stability degradation.

In terms of spectral properties, Chiguard® 9735 features an absorption peak ($\lambda_{max}$) at approximately 310 nm, covering the UV wavelengths most significant to material aging. Additionally, it is a pale yellow liquid, offering handling advantages over powder additives in automated dosing, mixing, and dispersion, which enhances process stability and formulation consistency.

With its excellent structural compatibility and processing ease, Chiguard® 9735 is widely used across various polyurethane sectors, including PU foam, PU leather and films, PU coatings, and PU boards, effectively balancing weather resistance with appearance stability.

建議您使用以下瀏覽器觀看本網站,

要下載瀏覽器,請直接點擊以下:以獲得最佳瀏覽效果。